THE DIGITAL NOMAD

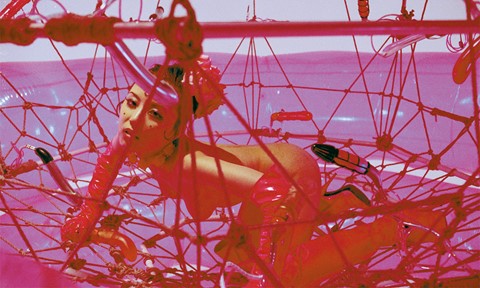

In UKI, Shu Lea Cheang’s latest feature film, Reiko, a defunct sex worker and replicant, is dumped in a giant landfill for electronic waste in the year 2060. Discarded because they have become obsolete as a collector of data on orgasms, Reiko attempts to regain control of their hard drive body, which experiences glitches and reshapes itself. Reiko ultimately transforms into a virus to save the planet from the ruthless plans of a biotech company.

Shifting between worlds and body types, narratives and characters like Reiko are common to many films made by Cheang, who as an artist, filmmaker, and networker is herself a border crosser. For more than 40 years, she has blurred the lines between art and film, between hack activism and queer science-fiction cinema, between feature film and pornography.

In homage to Shu Lea Cheang, FILMFEST MÜNCHEN is presenting five of the films she’s made since the 1990s—including short films and three feature films. Her latest production, UKI, will celebrate its world premiere at the festival.

Uki

Born in Taiwan in 1954, Cheang earned her bachelor’s degree in history in Taipei in the mid-1970s and subsequently moved to New York City to study film. Shortly thereafter, she joined Paper Tiger TV, a collective that broadcast live weekly programs on public-access television. Grassroots in nature, the collective sought to revolutionize television by playfully challenging its underlying ideologies in a do-it-yourself approach. These forms of activism, of collaboration, and a critical awareness of mainstream media remain part of Cheang’s outlook today. Her operating radius has simply adapted to the technological developments and media available at a given time, such as by expanding into the networks of cyberspace in the late 1990s. That’s when Cheang left New York and became a digital nomad—a “floating digital agent”, as she puts it. Since 2004 she primarily lives in Paris.

Cheang created the first Web project for the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York: “Brandon” (1998–1999) was a kind of interactive website in memory of Brandon Teena, a young trans person who was raped and murdered in Nebraska in 1993. Since then, Cheang has not only been considered a pioneer of so-called Net Art; she is certainly a pioneer of queer new media art as well, because she demonstrated early on that filmmaking as well as digital art is not a desolate landscape of white patriarchal heterosexual male sensibilities. For several decades, her various projects have also been devoted to issues that seem all the more topical today, such as the effects of technology on our bodies and our interactions with one another. “Shu Lea’s methodology is unique in its way of connecting two ends that are usually not connected at all: on one side queer history and politics, queer trans activism, and on the other side the digital geeks, the hack activism—bringing them together through fiction and poetry,” says philosopher Paul B. Preciado, whom Cheang invited to curate her exhibition as Taiwan’s representation at the Venice Biennale in 2019. Her immersive installation “3×3×6” explored incarceration and the digital surveillance of prison cells in relation to gender and sexual nonconformity. This made Cheang the first person not perceived as male to represent Taiwan at the Biennale with a solo exhibition.

She is no stranger elsewhere either. Her works have been shown at international festivals such as Sundance and the Berlinale, exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum in New York City, the ICC in Tokyo, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and presented at biennials and art shows such as the Documenta in Kassel and the Gwangju Biennale.

Sex bowl

Sex fish

Even in Munich, her work is familiar. Last year, Museum Brandhorst presented a remake of her installation “Those Fluttering Objects of Desire” (1992/93) in the exhibition “Future Bodies from a Recent Past—Sculpture, Technology, and the Body since the 1950s”. Inspired by peep show video booths and telephone sex hotlines, the exhibition featured works by more than 20 artists, filmmakers, and writers from Cheang’s own circle of New York acquaintances.

Many individuals from the queer feminist scene also appear in her early films, of which SEX FISH (1993) and SEX BOWL (1994), created in collaboration with Ela Troyano and Jane Castle, are being screened at the Filmfest. These works deal with various forms of queer bodies and encounters between them. Set in early 1990s New York, where people rarely talked about sex and bodies without prejudice in the face of the AIDS pandemic and lingering racism, Cheang’s films portray a queer community with sexual agency. They address eroticism and desire apart from a patriarchal gaze of the camera. “I was trying to break away from the notion of sex as taboo,” Cheang said in an interview.

Her later films continue to pay particular attention to queer sexuality and the disappearing boundaries between private and public intimacy. She additionally relates these themes to questions about evolving technologies, global Internet capitalism, and political control and surveillance. Cheang’s second feature film, I.K.U. (2000), takes up where Ridley Scott’s famous cyberpunk film BLADE RUNNER (1982) left off. A cyberpunk science-fiction porn film, I.K.U. is about orgasms as commodities in an age of digital technology. Like many of her films, it twists conventions of porn while defying categorization. “As much trans-genre as it is trans-gender, I.K.U. also wants to merge video and film into a fresh digital universe large-scale enough to overwhelm the viewer.” She definitely succeeded in overwhelming the viewers. At I.K.U.’s world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival, almost half of the audience left the theater because of the explicit sexual acts in the film.

I.K.U.

FLUIDØ

Her third feature film, FLUIDØ (2017), also had difficulties with censors in the United States. Here the human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) have mutated and the ejaculated fluid becomes a drug and commodity;. Only excessive masturbation can collect and spread the desirable substance.

In her latest film, UKI (2023), orgasms are only possible when people shake hands and take red pills. UKI has been in development since 2009, at a time when the idea of cyberspace as a utopia had long since gone out of date and Cheang had retreated into the post-Net crash BioNet zone she postulated in order to concentrate on viral love and bio-hacking. As a feature film, UKI was made over many years in an iterative process involving a viral performance, a collective multiplayer game, and various editions of installations. “I am crafting a genre of sci-fi new queer cinema in which sex, code, and data intersect in an entangled [science] fiction” is how Cheang describes it. Her works infuse science-fiction narratives with a radical queer perspective that uses new technological means in a critical way and is not afraid to break sexual conventions and question social norms.